☆ Opinion: looming Bay Area sales tax hike ignores massive overspending on transit

Public transport ridership has tanked in the Bay Area, but spending has more than doubled, inflation-adjusted, since 1980. So says former transit executive Tom Rubin in an Opportunity Now exclusive op-ed. The RM4 dragon-slayer calls on voters to insist on improvements first, before considering new taxes.

For decades, the Bay Area Transit-Industrial Complex (BATIC) has been totally mismanaging government surface transportation, producing major reductions in transit ridership, worsening traffic congestion, making getting-around worse for travelers and goods movements while substantially increasing costs and taxes. BATIC has been very successful in increasing the financial well-being and power of its component groups: transit operating and construction trades; construction firms/suppliers, architecture/engineering/planning firms, attorneys, investment bankers, and the elected politicos they support.

Transit ridership has decreased substantially since COVID began while costs have continued to increase. The powers-that-be have refused to institute structural changes to keep vital transit services operating costs down, so the decision-makers came up with their ideal solution: protect BATIC by keeping doing wasteful things, but increase taxes through the-sky-is-falling rhetorical arguments.

Government surface transportation in the Bay Area is handled by literally hundreds of different cities, counties, and special districts, plus various State and Federal agencies, with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) responsible for coordinating its planning, funding, and operations. MTC is currently finalizing Plan Bay Area 2050+ (PBA 2050+), its fourth quadrennial nine-county transportation – and housing – plan. As with its predecessors, PBA 2050+ is a cheerleader document, evidently prepared by the love child of Pollyanna and Dr. Pangloss, designed to show that the impossible can be done – in a plan that will immediately be disregarded and, MTC hopes, forgotten.

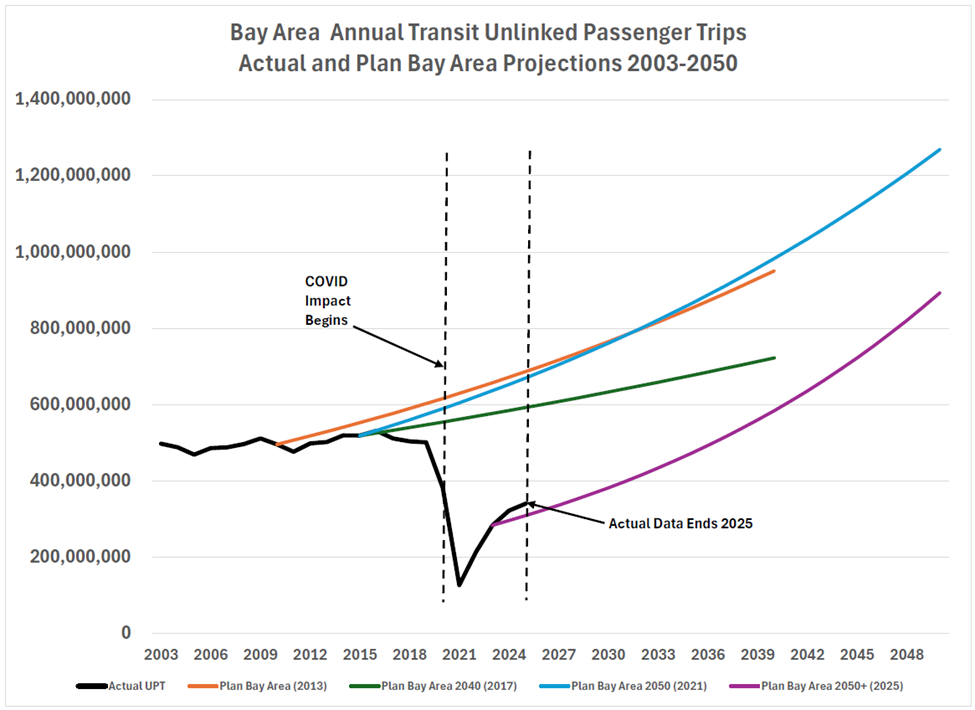

Let’s take a look at MTC’s record in projecting transit ridership; the graph below shows the projections from the three previous and current PBA against actual ridership:

Bay Area transit ridership had been very stable at roughly half a billion annual unlinked transit trips from 1980 to the last pre-COVID year, 2019 – even as the Bay Area population grew over 50% during this period. Transit unlinked passenger trips (UPT) per capita fell over 30% over this period, but transit usage fell even further as the BATIC prioritization of high-cost long-haul transit “improvements” such as BART, light and commuter rail, and ferry service forced transit users to more transfers, increasing UPT per linked origin-to-destination trips for commute-to-work, school, health care, and other purposes.

Despite this record for vastly overstated ridership projections, MTC has consistently projected substantial future ridership increases – and, when they did not appear, the only adjustment in subsequent projections was to reset the beginning year to actual for the start of the forecast period.

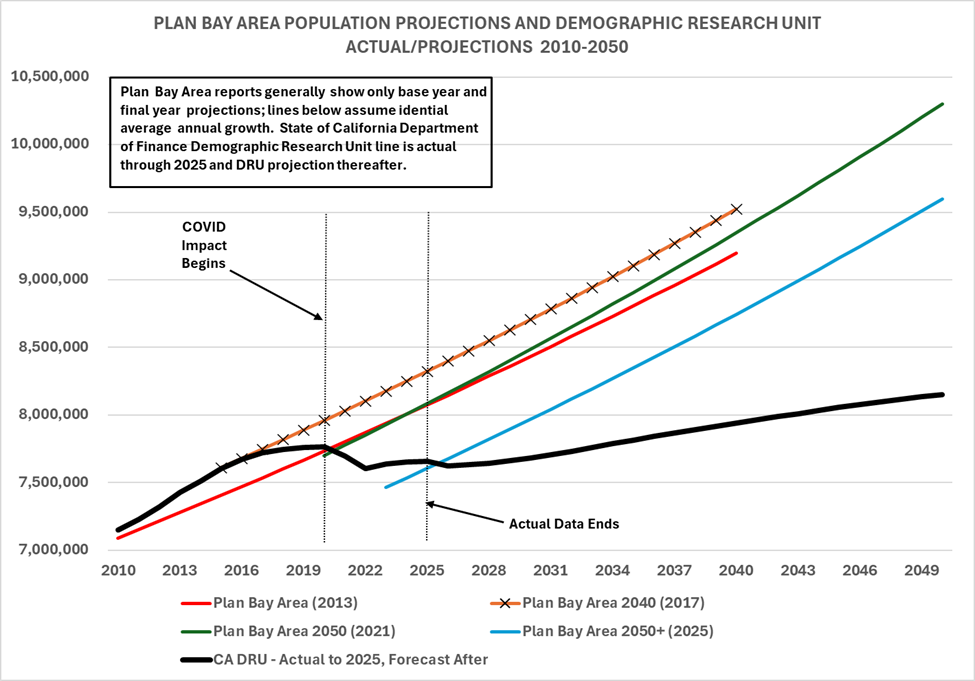

Part of this increase in transit ridership has been due to MTC’s equally incompetent large population increase projections:

Bay Area population growth has slowed substantially since approximately 2016, actually had a decrease during the COVID years, and – with the sole exception of MTC – no organization is projecting more than minimal growth, if any, over the upcoming decades. MTC uses these unrealistically high population projections to drive higher projections of revenue growth, road congestion (see following graph), transit ridership, and the need for more housing (MTC’s latest responsibility, transferred to MTC by the California Legislature, evidently justified by the outstanding job that MTC has been doing for its initial responsibility, roads and transit).

The BATIC transit emphasis has certainly achieved part of one of its objectives. Since BATIC understands that it is impossible to make transit competitive with driving for most choice transit riders by improving transit, the obvious alternative is to make driving worse – slower, more unreliable due to unpredictable congestion, more expensive through higher gas taxes and tolls, and reduced/more expensive parking. Well, as the above shows, MTC et al have certainly been successful in making driving slower and driving times more unpredictable, but, while transit usage is still far below pre-COVID levels, driving in the Bay Area had returned to, even exceeded, previous levels of congestion, by 2024 – and some new drivers were previous transit riders.

While transit ridership has tanked, transit spending has significantly increased, well over doubling, inflation-adjusted, since 1980 as BATIC pursues ever-more-expensive and failed major capital projects, including (all cost comparisons inflation-adjusted):

Dublin/Pleasanton BART extension cost increasing by over two-thirds

Warm Springs BART extension’s cost increasing 92% – and being completed 25 years after the taxpayers approved the tax to complete it

BART Oakland Airport Connector costing almost half a billion dollars, which is 154% over the original budget, opening 24 years after the taxpayers approved the tax – for the second lowest ridership of BART’s 50 stations, at substantial operating subsidy, replacing a very workable shuttle bus system that came close to being paid out of farebox revenues (the fare doubled when the Connector opened, which drove away many former riders)

BART Warm Springs-Santa Clara extension increasing in cost from the original $3,710 million to over $15 billion – four times higher – while the projected opening date has slipped thirteen years between the now-disowned 2021 projection to the current (and questionable) 2039 date – if it is ever completed

The Salesforce Transit Center in the San Francisco Central Business District cost over $2.2 billion, approximately 50 times the projected costs for seismic safety upgrades to the original Transbay Terminal – and wasn’t opened for service until three decades after the 1989 Lorna Prieta earthquake that ultimately lead to shutting down the original (Salesforce opened in 2018, but quickly shut down until cracks in the beams supporting the “third floor” bus level over Fremont Street were fixed)

BATIC is still working on a Caltrain/California High-Speed Rail station in Salesforce – at a currently-projected (but hardly guaranteed) cost of $7.5 billion (which includes the $729 million for the completed but unused station box) – to extend the rail line approximately 2.2 miles from the current Caltrain terminal at Fourth and Townsend, where it is well served by multiple transit options, including light rail, to the San Francisco business district

The taxpayers must insist on improvements first – then taxes:

Substantial changes in bargaining agreement work rules

Increased usage of part-time operators

Implementing full autonomous operation of BART trains

More contracting out for transit service

Reduce administrative costs

Stop expensive planning of what will never be/should not be built – Link21, Valley Link, BART to Santa Clara

Follow Opportunity Now on Twitter @svopportunity

We prize letters from our thoughtful readers. Typed on a Smith Corona. Written in longhand on fine stationery. Scribbled on a napkin. Hey, even composed on email. Feel free to send your comments to us at opportunitynowsv@gmail.com or (snail mail) 1590 Calaveras Ave., SJ, CA 95126. Remember to be thoughtful and polite. We will post letters on an irregular basis on the main Opp Now site.